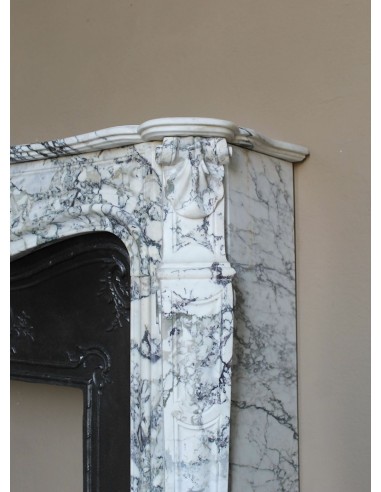

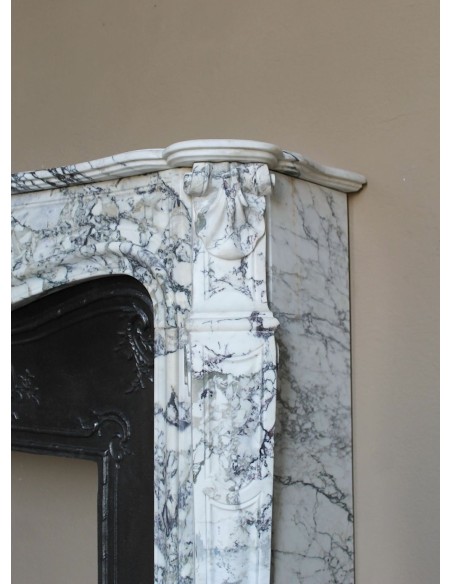

For a long time, I had been waiting for the opportunity to comment on this splendid Trois Coquilles model, dressed in a marble as refined and as coveted as this Calacatta Gold — especially coveted by our wives. Its white tone is closely related to Carrara Statuario marble, yet it displays even warmer nuances, closer to ivory.

Equally fascinating are its numerous elegant veining patterns, ranging from grey-black to yellow-red. All these refined shades are the result of the presence of iron oxides (which, in this case, produce red or pink tones), sulfur oxides (responsible for more yellowish hues), or so-called clay minerals — please don’t ask me to specify which ones exactly, as chemistry was never my strongest subject — which give rise to the classic grey-green tones characteristic of Calacatta marble.

The artistic cast-iron insert is also of great interest and features two decorative elements worth highlighting.

The first is the stylized heart at the center of the upper horizontal band (clearly visible in the fourth-to-last image). This heart was intentionally designed by the architect-designer of the insert to allow the wealthy purchasers of this fireplace/insert pairing to engrave their name, initials, or even their coat of arms. Fortunately, these owners proved themselves to be true gentlemen and refrained from marking our fireplace with any ostentatious personal emblem.

The second noteworthy element is the finely designed Roman fasces motif decorating all the borders of the insert. Its meaning is not military, fascist, or political in nature. At the time this fireplace was made (the Napoleon III period, second half of the 19th century), this symbol — notably without the double-headed axe — literally meant “Unity makes strength.” It referred not to warfare, but to the fundamental importance of family unity, the greatest good of all.

And, if I may add, the fact that this symbol frames the family hearth speaks volumes in itself.

We have already discussed its period of creation (repetition helps: Napoleon III period, second half of the 19th century). The fireplace was discovered in Paris, on Boulevard de Clichy, practically at the foot of Montmartre. Its state of preservation is truly excellent and, dulcis in fundo, as is so often the case with pieces of this quality, its carving was carried out in the thoroughly Italian, industrious, and exceptionally skilled Lunigiana — a land that, from 399 BC to the present day (not merely a world record, but almost a cosmic one), has been continuously unrivaled in the quality of its sculptural tradition.